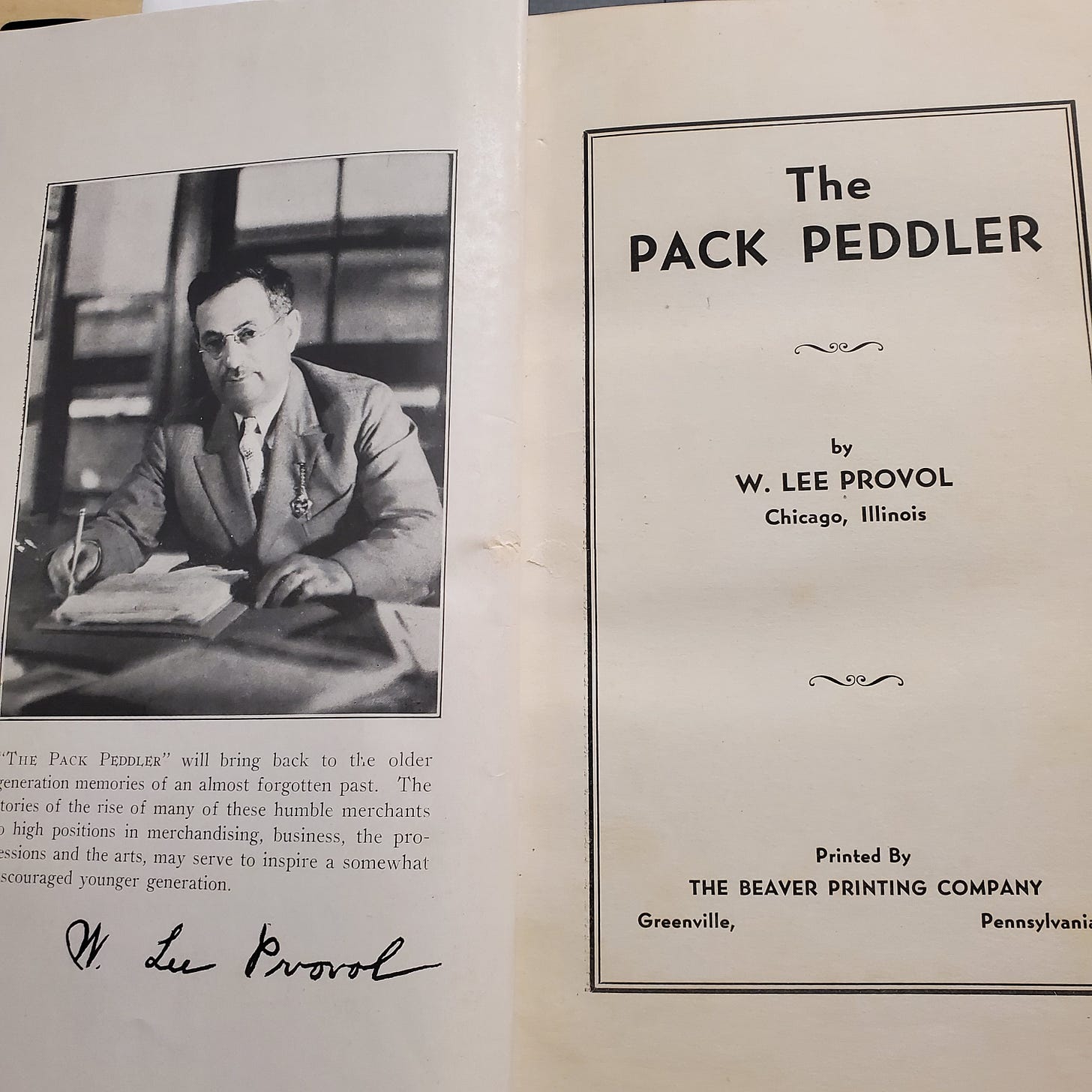

Recently, my research turned up a fascinating book, Pack Peddler by W. Lee Provol. Even at its publication, seems to have had a very small run and to have been of interest primarily to people who actually knew the author. The first copy that arrived via Interlibrary loan (one of the best things in the world, in my opinion, as it makes almost every text available through almost every library) was so poorly cared for that the librarian sent it back because it was turning to dust. The only other copy we could find arrived last week, and while it’s in better shape, the spine is tender enough that I have to read it half-open and carefully. I ordered a pair of cotton gloves, the kind archivists wear, so that the oils in my hand wouldn’t ruin the pages. When I come to pages that can’t be opened without damaging the book, I skip them. It seems as much talisman as text.

Published in 1933, this book is very much of its time. The language is stilted in many places, and Provol goes to great lengths to quote the more famous writers of his time, tying himself not so much to the Jewish traditions (though it is a very Jewish book) but to the American moment. In it, one reads all the hope of Jewish immigrants from the Great Migration era and their faith in the United States as a place where Jews could live as equals and in community with others, as opposed to the conditions they’d left in Europe. “The Statue of Liberty in New York thrilled me, at the first sight of it, as an immigrant boy, but it thrilled me more to see it on my return trip from the old homeland,” he writes. It’s a deeply patriotic book, though one can feel in its patriotism a plea: please agree with me that this is, indeed, a place where Jews can live as equals and in community, my fellow Americans.

It’s also—and this is very rare—an account of role of pack peddlers in American communities and lives of Jewish immigrants to the US, written on the cusp of, but before, WWII. It is, among other things, a heartbreakingly naïve book that wants to insist we needn’t worry too much about the rumors coming from Europe, as “we” are safe in the US. It’s understandable—it was only 1933, after all, and he is writing this book in no small part for his own children, to whom he wants to give hope and an appreciation of their lives in the US—but it’s also tragic when read through the lens of history.

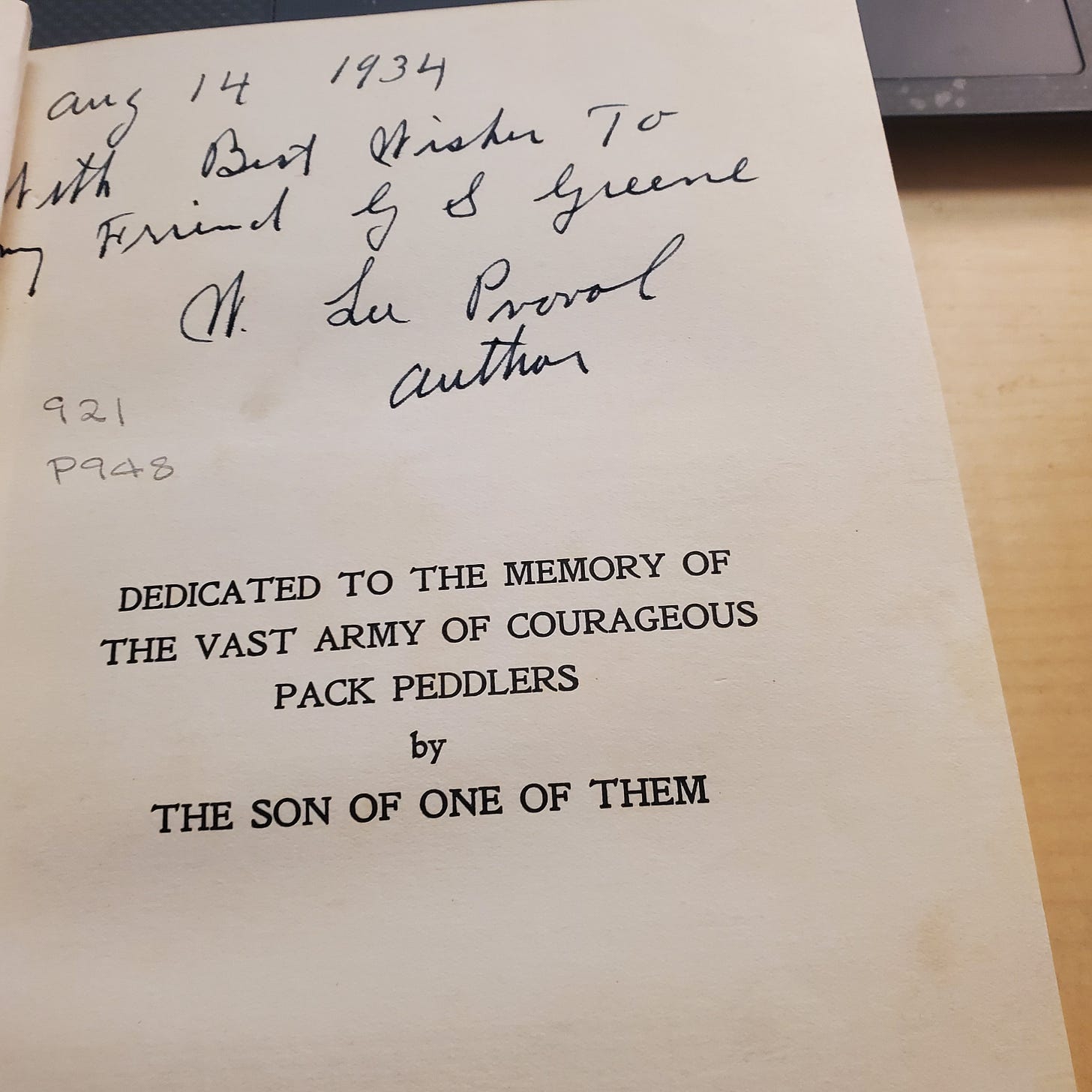

I would love to recommend the book to you, but I’m not certain you can find it, and that I don’t have in my possession the only copy available via interlibrary loan that isn’t in unreadable shape. And what a copy it is, signed by the author to a friend:

And now I’m going to ask you for help with a moral dilemma, friends. I have, in my hands, this wonderful book that hasn’t been checked out—according to the records of the host library—by anyone. In fact, the stitching on the spine shows that not even the person to whom the book was given read it all the way through. Do I just keep it and pay the replacement cost, handing it off to a collection of Jewish books where it might get some readership, or do I abide by the code of borrowing from libraries and return it from whence it came, and from whence it might never be read again? What would you do, friend, confronted with a rare historical account from a pivotal moment in our/your people’s history that might be better placed in an archive than library? Help me make this decision?

Since the copyright has expired, I would use a scanner or the Notes app on my iPhone to create a PDF of all readable pages, post this online for anyone to access, and then return the book to the library.

Well, as a natural born crook, I would keep it, pay the replacement cost, and give it to a place where it will be respected and used. Should the replacement cost be too high, just write them and say “well look at that- I found it!” and give it back.

Love, Mom